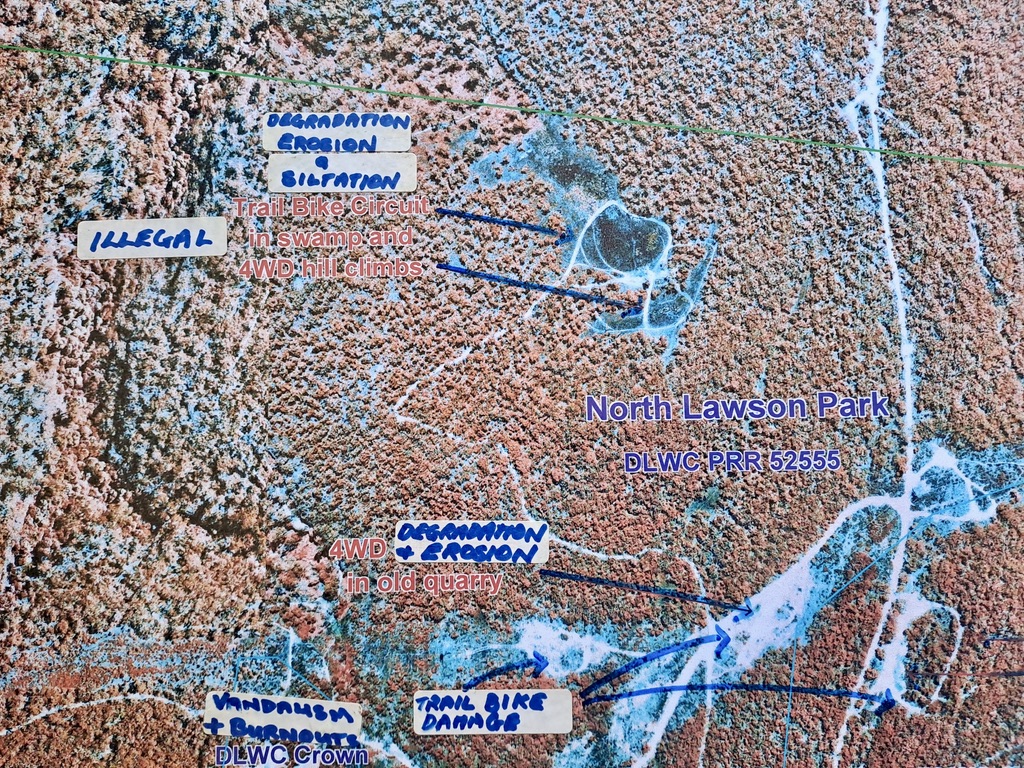

Jeanine and John revisiting photos of damage and degradation in North Lawson Park caused by illegal vehicle encroachment

Story and photographs by Belle Butler

Eyes closed, sitting still on an overgrown track at the side of a swamp in North Lawson Park I could hear the wind approach. The distant treetops gave it away: both the direction it came from and how close it was. When the gust arrived, it buffered me along, childlike in the way it showed off and demanded attention, shaking all the trees at once and drowning out the sounds of everything else.

Impulsively it charged on.

When it was quiet again my ears sought out the other sounds. Birds mostly, their unique call and response. Call… call… call and response. The wind returned, teased the sedges then raced away. Something unknown rustled in the nearby leaf matter and compelled me to open my eyes. Not a snake. Good. I closed them again.

Peaceful surrounds at the hanging swamp in North Lawson Park

Then it became so quiet I felt like I was reaching out for a sound, something to place me there on the crumbling remains of regenerative coconut fibre coils upon which I sat. Waiting for a bird to call or the next show-off gust of wind. Then something arrived. My ears latched onto it, a strange tap, tap, tapping noise. Too regular for the arhythmic sounds of nature, I decided.

So I opened my eyes again. Looked around. Expected to see a person, maybe a kid hitting the ground with a stick. Only I was wrong. Just off this old track and partially hidden in the sedges of the swamp was a wee fairy wren with a fat worm in its mouth. It stood on a log, worm in beak, and whacked it against the wood… tap tap tap. Lucky wren. Not so lucky worm.

Video: A listening experience at North Lawson Park

When I left the swamp and five minutes later arrived at my home, I felt like I’d been a great distance away, renewed and reconnected as if returned from a holiday. The quiet of the Blue Mountains bush can do that to you.

I am grateful for it, although I am guilty of taking it for granted. And this swamp, these tracks were not always the peaceful escape they are now. They were not always the safe haven for a hungry wren.

In the early 2000s North Lawson Park was used as an off roading circuit for 4WDs and trail bikes. “It was like listening to a chainsaw the whole time,” said Jeanine Redfern, who, with John Sheehy, lives in close vicinity. “The walking tracks were dangerous to take our children on, because you never knew if the motorbikes were going to run you over.”

4WD going up the quarry wall (supplied)

The same quarry walls are now used as climbing apparatus for local kids

The vehicles accessed these trails via the end of San Jose Avenue and St Bernards Drive. Their main areas of usage were the grassy flats above Fairy Falls, the old quarry and the nearby hanging swamp.

Damage at hanging swamp caused by trail bikes (supplied)

4WD damage at the hanging swamp (supplied)

John and Jeanine have a strong connection to the bushland that extends from the street they live on, having spent many hours of many years walking the trails and enjoying the surrounds. They value the serenity and the distinctive significance of the environment. “The Blue Mountains environment is so fragile,” said John. “It’s bad enough with humans walking on it, but when you get trail bikes and 4WDs destroying the bush, you see the damage overnight.”

Jeanine and John pointing out particularly damaged areas on an aerial photograph of the region taken in the early 2000s

It is shattering to witness the swift destruction of something that has existed for millennia. Pangs of regret are particularly sharp when the destruction is caused by our own species, which is often the case. Even though we are here, individually, for only a short time, we have the power to devastate the things that predate and outlast us.

When John and Jeanine witnessed the rapid destruction of the environment they loved due to vehicle encroachment, they felt desperately saddened. And enraged. Sitting in their living room, John took me through VHS footage of what they witnessed: trail bikes speeding off into the bush, 4WDs trampling vegetation and mounting the steep rise of the quarry walls, discarded bikes thrown into the waterways. The delicate soils of an ancient swamp churned up in 30 minutes. Watching it again, John and Jeanine shook their heads. “It broke our hearts really,” said Jeanine. “This is supposed to be a World Heritage Area, and look what was going on.”

Damaged hanging swamp (supplied)

Discarded bike above Fairy Falls (supplied)

The rapid destruction of the hanging swamp is what prompted John and Jeanine to act. “In the whole of the world, you only find them in the Blue Mountains. They’re very unique,” said Jeanine. John added: “They’re at the core of our environment, central to the plants and animals that are here.”

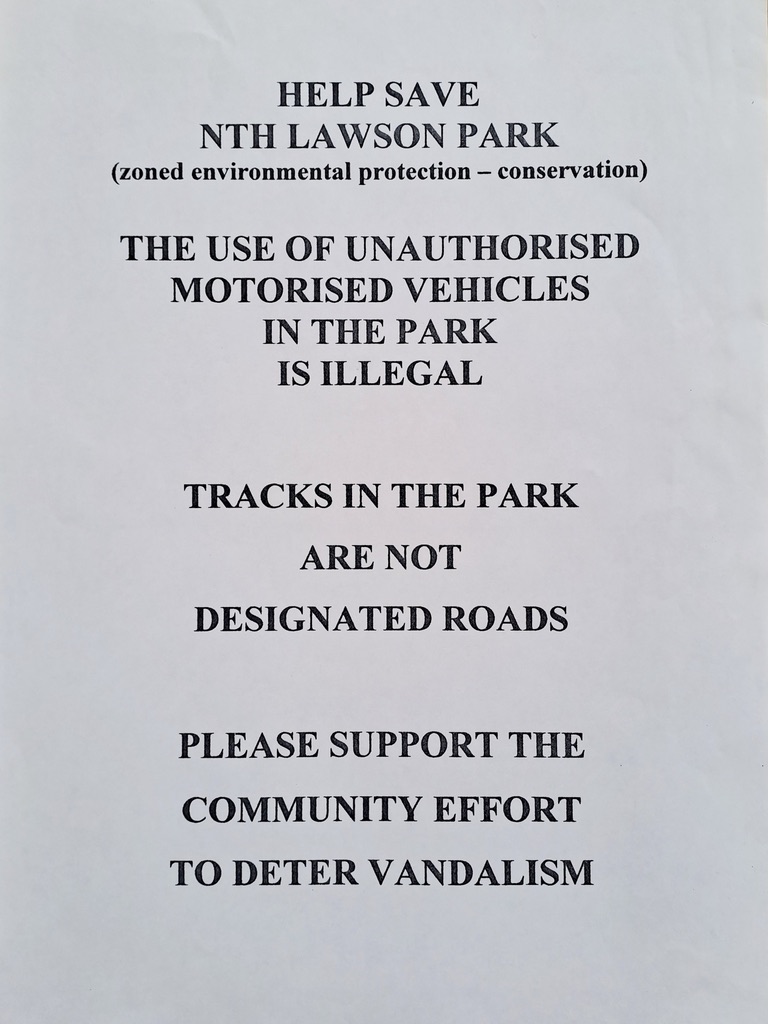

Initially, they tried to make perpetrators aware of the consequences of their actions by talking to them and putting up homemade signs. “From sheer exasperation I’d go down and speak to these people, down at St Bernards Drive while they were driving and having big bonfires. If you go down St Bernards Drive now, you can see it’s still denuded, still bare – that’s a result of all the burnouts,” said John. Jeanine too used to stand her ground on the tracks and take photos of drivers as well as their number plates, if they had any. However, their proactive approach was not well received. They were ignored, verbally abused, at times threatened. One man tried to punch John.

A homemade sign John and Jeanine placed at the entrances to North Lawson Park

Official council signs later went up as a result of the campaign

This kind of reception made it an unattractive prospect for other members of the community to get on board: “We asked others to help, but everyone was too scared,” said Jeanine, who acknowledged she didn’t scare easily but found the whole situation untenable. It had an impact on her mental health and at one point she said to John, “I can’t live here anymore.”

Recognising the need for support, they initiated a public meeting, inviting the community, The Blue Mountains Conservation Society, National Parks and Wildlife Services and Blue Mountains City Council. “What really helped our cause was the hanging swamp,” said Jeanine. “That really got the Conservation Society behind us.” John added: “We really appreciated the support of the Conservation Society, which was absolutely essential in getting things happening.”

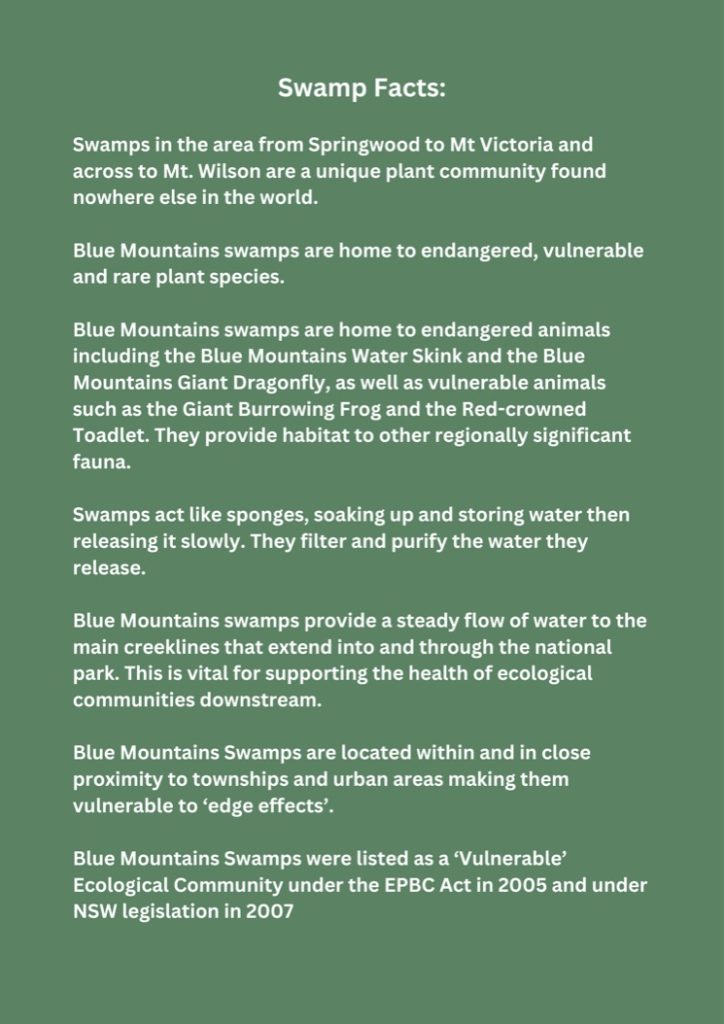

At the time, the Blue Mountains Conservation Society was pushing for Blue Mountains swamps to be listed as a ‘vulnerable’ ecological community under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act. Awareness of their important ecological function was on the rise.

The swamp was at risk of drying out (supplied)

Community and agency support grew into a collaboration as a result of the public meeting and growing awareness that North Lawson Park was a habitat for the endangered Giant Dragonfly and the vulnerable Persoonia acerosa (needle geebung), as well as potential habitat for the Blue Mountains Water Skink.

The vulnerable Persoonia Acerosa (needle geebung) growing on the side of the track

Moss now growing on an abandoned bike jump at the quarry

It took two years of persistent activism and care, but the push for change resulted in gradual improvements. Blue Mountains City Council put in gates and signage at the entrances to the Park, curbing some of the damage. “Motorbikes continued to come in, but not like they used to,” said Jeanine.

Vandalism to Blue Mountains City Council mitigation measures (supplied)

On occasion drivers would use post removers to physically remove the gates, or simply knock them over by ramming into them with their 4WDs. “But the police and fire brigade ended up being really supportive too, and we just kept at it,” said Jeanine. “The big plus was people started using the tracks for walking. And the more people used it for walking the less motorbikes used to come.”

Once the damaging activity reduced, talks with Blue Mountains City Council about regenerating the swamp began. Water flow had significantly altered and erosion was creating sedimentation problems in the reeds. “The racetrack had cut off moisture from going into the middle of the swamp,” said Greater Sydney Landcare’s Xuela Sledge, who worked with National Parks and Wildlife Services at the time and was an advocate for the restoration campaign. There was a chance the swamp would dry out. “Those swamps take a long time to get to that point,” said John. “We were concerned that it wouldn’t recover. And it’s still not fully recovered. It takes about 50 years we’ve been told.”

Restoration efforts on badly damaged section of hanging swamp

Comparison shot – Jeanine standing where 4WDs had badly damaged the hanging swamp.

In a final-push collaborative effort, local residents, Blue Mountains City Council staff, National Parks and Wildlife Services and the then federally funded program Green Corps all came together on January 30 2002 to repair the swamp. They levelled out potholes and mounds created by the bikes, then installed long coils of coconut fibre, coir matting and sandbags to realign the water flow back into the swamp. They relocated some of the sedges in order to prompt revegetation of damaged areas.

Coconut fibre coils were used to help restore the hanging swamp

It’s been just over twenty years since then. Today, the track to the swamp is narrowed by encroaching vegetation and has become the home of busy ants and Drosera plants. It peters out completely down among the sedges where you can still find the decomposing remains of coconut fibre coils.

Tracks are now the happy home of ants.

Healthy Drosera plant now growing on the old ‘racetrack’ at the swamp

Revisiting the site with Xuela and Jeanine, it was delightful to see their pleasure in the outcome of their efforts. Standing at one of the worst damaged areas, they recalled witnessing the emerging of a Giant Dragonfly from its chrysalis, how they stood there for so long to see the whole process evolve and finally to watch the Dragonfly stretch out and air its newly expanded wings. Good things are worth waiting for.

“It’s a real success, both socially and ecologically,” said Xuela, “getting the whole community involved in respecting this ecological type. And the swamp has restored itself so beautifully. It’s functioning really well.” Jeanine was relieved by this and by Xuela’s confirmation that the vegetation appears to be weed-free. She explained that the sandstone makes it difficult for the weeds to infiltrate the area. Jeanine also shared that this was the first year they had witnessed water flowing back over the disused trail bike ‘racetrack’.

Xuela revisiting the swamp: “It’s a great example of community instigating change and standing up for the local environment.”

Xuela and jeanine on the now disused ‘race track’.

Reflecting on their efforts, John and Jeanine shared mixed feelings. “I’m so glad it’s over,” said Jeanine. “I couldn’t stand that being my life. I liked it once we got the different groups on board and the act of restoring it, but we had at least two years before that of chasing bikes and 4WDs, putting stuff on the track, telling them they weren’t allowed. I mean, that was my life. But in the end, it was a great outcome.” John concurred: “It was full on. But you’ve gotta be active,” he said. “Unless local people do something about what’s happening in their local area, this kind of stuff gets really out of hand.”

Aerial of damaged swamp and other degraded areas in 2001

Aerial of hanging swamp 2018 (credit NSW State Government)

Just as our species has the power to devastate, we also have the tenacity, if we are persistent, lucky, and get in soon enough, to repair. In this case, the ongoing efforts of John and Jeanine, the local community and the various groups involved have had an outstanding outcome, the value of which cannot be quantified. As I sat in the quiet, noticing the ants, the wind in the sedges and the catch of the hungry wren, I felt genuinely grateful.

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.