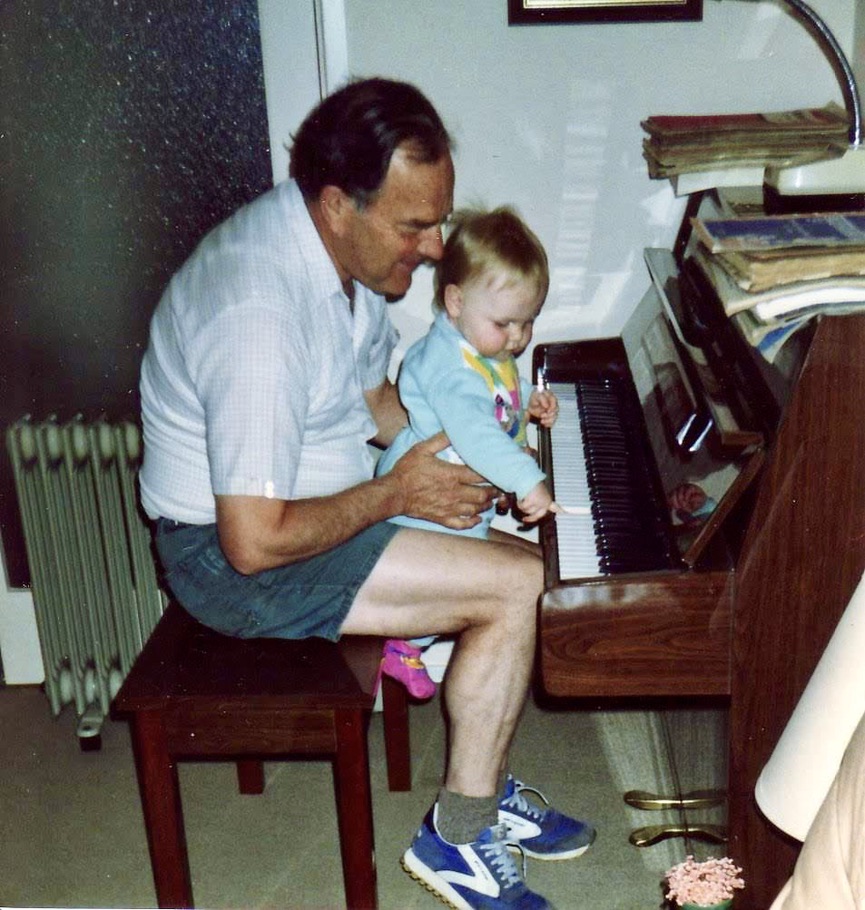

Belle’s daughter Nahla at the ‘new’ piano (Belle Butler)

By Belle Butler

When I was a teenager, I’d have long, angsty chats with my grandmother’s table mirror. I was a rather awkward figure: dressed all in black, my long hair pulled forward to provide an adequate curtain to hide behind, black eyeliner no doubt streaked down wet cheeks. I’d sit on my mother’s bed, grasping the floral brass rim of that mirror and go through all the tangles of my deepest thoughts.

It might seem odd, especially as I never met my grandmother. She died at 49 from pancreatic cancer, two years before I was born. But I’d been told by people who knew her that I shared some of her qualities. So, when I felt most alone in the world, I used this material connection to her to feel less so.

The thought of that mirror possibly ending up on a heap of landfill one day physically hurts my chest. There is more value in it than the sum of its parts. There is the life of my grandmother, Ruth, recalled every time I see the mirror. There is also my own (embarrassing) recollection of teenage deep-dives into self-loathing and tales of unrequited love, that, much as I’d like to forget, are a part of my life. And there is the story of my own mother too – how she was heavily pregnant with my brother and overseas when Ruth was sick, how she had to get medical permission in order to fly back and be there while Ruth died, how afterwards, she had to rush back to London to have a baby instead of grieving with her family, and how that mirror was one of the only items of Ruth’s left to her.

There is obvious sentimental value in retaining an item like that and passing it on through the generations. When I look around my home, I realise I have been the recipient of many such items. From rugs to furniture, there is almost nothing new in our house. Of note is an old desk that belonged to my grandfather. When I was cleaning it, I discovered my ‘Pa’ had written his name on a hidden bit of slide-out wood and dated it in 1941, and that my father had done the same thing 28 years later. Perhaps it’s my turn now.

Tucked away in my grandfather’s desk, a piece of wood signed by him in 1941, then by my father in 1969 (Belle Butler)

It’s not just family heirlooms that I have so enjoyed the company of in our home, but also other used furniture I have picked up (or rescued) along the way, most recently a mahogany-coloured Kawai piano from Facebook Marketplace.

‘Too beautiful for the tip,’ the ad said. After a few back-and-forth messages with the owner, and a visit down the hill to Woodford, I found myself shifting furniture to accommodate the new arrival.

The piano spent a few days sitting awkwardly, teenager-like, in the middle of our living room. One centimetre narrower and it would have tucked into the nook I had in mind, but alas, used items come ‘as is’, not custom-made. So here it was, uncompromisingly itself, getting in our way as we traversed the living room, slowing us down. Inviting us to stop and get to know it.

Getting our new/old piano tuned. “Look after this one and it’ll last you the rest of your life.” – Glen, the piano tuner (Belle Butler)

My daughter and I both found ourselves pausing at it throughout the day. I was particularly drawn to the bass notes, which have an amazing warmth that resonated in my chest. My daughter tinkered around with fairy-like melodies in the higher notes. I stopped what I was doing to listen.

Of course, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, pianos were commonplace in homes and were a central point of social life. Ordinary people of all sorts learned to play, and performance was a way to connect, a form of everyday entertainment. After a few family meetings about the final residing place for our new/old piano, we decided it needed to stay in the heart of the house, where anyone and everyone might pause for a moment and play something. So, we rearranged our entire living room and placed it in the centre of everything.

The Kawai now sits comfortably and confidently in its new home. It already has a great success rate of drawing in hands. A little boy from up the road asks if he can come inside to play, and my daughter provides enforced ‘entertainment’ upon her friends when they visit. She and my son, who is learning the trombone, even had their first ‘jam’ having discovered they both know the riff from ‘Smoke on the Water’.

The piano’s superpower is to connect people. But there is another form of connection made when the piano, or instrument, or piece of furniture that comes into your life is second-hand. It was unexpected, but in getting to know this piano, I discovered an intense curiosity about the instrument’s past life.

The previous owner answered my questions and responded kindly to my (probably peculiar) curiosity. The piano belonged to her father, who she referred to as ‘a wonderful man’. She recalled him playing Black and White Rag and Scott Joplin and mentioned that he didn’t play much classical in his later years. She spoke of an upper-mountains friend, Allan Smith, who composed music and used to come and play it, how she loved hearing him. She even sent through pictures: one of her at the piano with her then teenage son, and one of her father gently cradling his young granddaughter as she pressed down a key.

Previous owner of the piano, Carole, with her son (supplied)

Original owner of the piano, Carole’s father, with his granddaughter (supplied)

My affinity broadened as I received these tid-bits of information. I realised there is a continuum of story that the piano holds within it – we receive it, we contribute to it, and hopefully we pass it on. Knowing a bit of that story adds to the richness of having it in our lives.

There is also the knock-on effect of reducing one’s ecological footprint. Production of new instruments requires resources such as fossil fuels, harvesting wood or use of plastics – all ongoing costs to the planet.

The company Kawai, for example, sources parts for their pianos from all over the world. The wood is obtained from dedicated forests in various locations. Wool for the hammers is usually sourced from Australia or New Zealand, while the keys are timber with manufactured laminate on top. The pianos are assembled in factories in Japan, Indonesia or China, before the final products are shipped to Australia. Even without a carbon footprint calculator, it’s clear the impact of producing one new piano is significant.

Obtaining a second hand instrument also reduces landfill, which, in the case of this lovely piano, would have been a silent tragedy and a great loss to us if it landed there.

Given the number of op shops in the Blue Mountains and the plethora of platforms on which pre-loved items are passed on, swapped and sold, buying second-hand is an efficient and easy way of contributing directly to a local circular economy.

If you are interested in finding anything second-hand, some of the local online options are: Blue Mountains, NSW | Gumtree Australia Free Local Classifieds; Facebook Marketplace; Facebook – Salt Vinegar, Salt Vintage; Facebook – Katoomba Buy Swap & Sell; Facebook – Pay it Forward – Blue Mountains NSW; Facebook – Blue Mountains & Surrounds Free & Cheap Stuff; Facebook – Reverse Garbage – Blue Mountains Online.

You may even get lucky and find a story attached to the new/old item you welcome into your home.

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.