Kris Newton amongst the lush summer growth of her Choko vine.

Story and photos by Belle Butler

As we face predictions of increasing natural disasters due to climate change, past events show that community-led recovery and preparedness is key to building resilience. Belle Butler talked with Kris Newton of Mountains Community Resource Network about how she prepares to reduce her own risk of disaster, and about MCRN’s pilot project Resilient Villages, which aims to equip communities with the skills and tools they need to take control of their own destiny.

Key Points:

- Kris Newton has created a rich and diverse edible garden to prepare her in the face of potential future disasters.

- Past experience and evidence shows that local communities are best-placed to drive the recovery/resilience-building process as it will be unique to the needs of their particular communities.

- Modelled on MCRN’s own experience of what works in community-led recovery (and that of other communities around the country after the 2019 bushfires), Resilient Villages provides participating Blue Mountains communities with support in community-led recovery, and preparedness for future events.

The sight of fresh green emerging from the charred soil and charcoaled trunks of a fire-ravaged landscape is a bold image of recovery after loss, one that is familiar to most of us living in the Blue Mountains. It is perhaps the ultimate symbol of resilience.

Resilience is defined as the capacity to recover effectively from shocks: personal or community-wide; or the ability of a substance or object to ‘spring back’ into shape. Indeed, when it comes to the Australian bush (historically) it generally doesn’t take long for new life to appear in stark contrast to the blackened aftermath of a fire, for fresh foliage to fill out the familiar shape of the bush again.

But when it comes to individuals and communities affected by fire or other disasters, the process of recovery, back to a life we value, is often lengthy and complex.

Kris Newton, Manager of Mountains Community Resource Network (MCRN), the peak body for community services in the Blue Mountains, has seen first-hand the short- and long-term impacts of disaster on community.

Kris works in the community sector building preparedness and resilience, and her individual choices also reflect a commitment to self-agency and preparedness. Her garden is a living testament to this, providing her with year-round produce as well as a ‘green barrier’ to provide some protection to her home should a fire move through.

Kris was flung into her role as manager of MCRN “feet first, into the deep end” in 2013 when she took on the job after 40 years living and working in Canberra. She thought the job would be a good “peri-retirement” option, but then the fires hit the Blue Mountains and “everything changed.”

In 2013, parts of the Blue Mountains burned in what was then declared the worst natural disaster in the history of the region. Fires in Winmalee/Yellow Rock and Mount Victoria put members of the community under genuine threat, destroying over 200 homes and damaging 286.

“I saw what happened to the communities in 2013. My sector is still dealing with the recovery from that,” she said. “People have no idea how long recovery actually takes.”

Following the fires, Kris observed a disconnect between how government dealt with recovery and what communities actually needed in order to recover and to prepare for future events.

Eleven years later, government programs are now emerging which fund projects like the Blue Mountains Planetary Health Initiative’s Disaster Risk Reduction Project and MCRN’s Resilient Villages. They go beyond the traditional government approach of ‘cleaning up’ after disasters and focus on supporting communities and individuals to be better prepared and have less damage in the first place.

Kris made the comparison that during the 2021-2022 Northern Rivers floods, many people would have drowned if it hadn’t been for locals getting out in tinnies/surfboards/canoes to help their neighbours.

“It’s the same in every disaster,” she said. “It’s the locals who know their neighbours, who know their local community services, who front up to the neighbourhood centre or community hall and activate the networks, who support injured wildlife.”

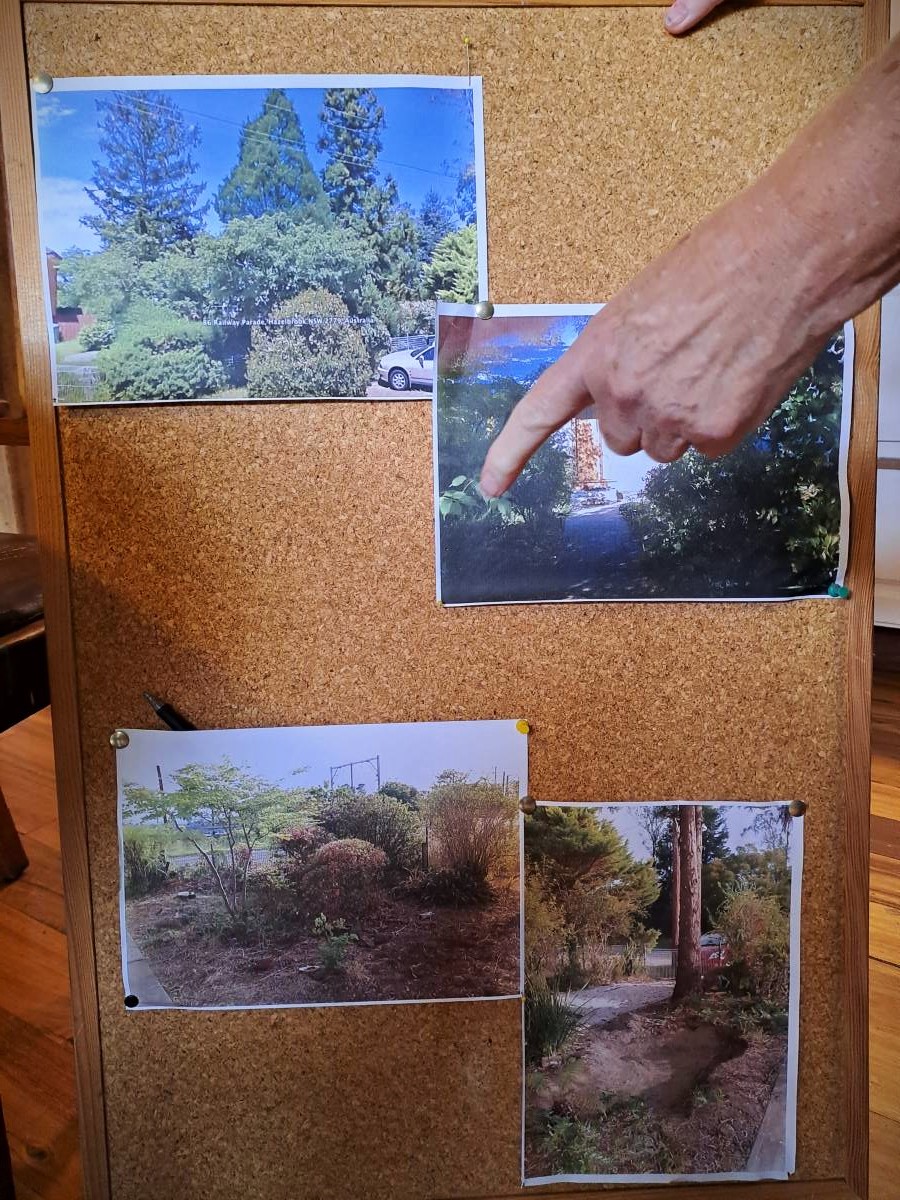

Kris showing the before pictures of her property in Hazelbrook, which was overrun with “every weed known to mankind.” Kris moved to Hazelbrook after 40 years in Canberra because you could “grow pretty much anything here” and has spent the last 10 years testing out that theory by turning her once weed-infested land into a thoughtfully designed edible garden that underpins her own self-preparedness.

Since beginning her role at MCRN, Kris has been advocating for a shift in the paradigm, where preparedness and recovery is government-supported, but community-led.

“The community needs to say: what are our priorities, what are the things that we value, what do we have in common, what is it that we love about where we live, and what do we want to protect? We might disagree about every other conceivable issue, but we do agree that we love and need to protect our community and here’s how we are going to do it,” she said.

Kris commended Blue Mountains City Council for their support for a paradigm shift since 2013 via programs such as The Birdies Tree, which brings preparedness learning into early childhood centres.

“Two main elements of resilience are: Firstly, ‘I have control, I have agency, I’m in charge of this, I’m in charge of life’; and the second element is community connections,” she said. “All the research (local, national, international) very clearly shows, that the more connections you have with your neighbours, friends and family, the better you are at coping with stress, coping with shocks.”

Her observations are echoed in a 2021 report on recovery since the Victorian Black Summer fires which advises governments to, among other things:

- Embed community-based strategies in disaster mental health planning, in addition to mental health services

- To maximise the contribution of social networks and community groups to recovery

- Prioritise restoration of places central to community connection, such as schools, community halls, sports and arts facilities and thriving local businesses

- Use social indicators of individual and community wellbeing and resilience, such as patterns of community group membership, for recovery planning

- Involve school communities in systemic and local recovery plans.

Hazelnuts and finger limes in Kris’s home garden. “I’m trying to be as self-sufficient as possible. I’ve got solar panels and solar batteries and water tanks and food. So if necessary, with the combination of fresh food, frozen stuff and things that I’ve preserved, I can last for quite a long time.”

The need for change became even more apparent and urgent when in 2019 an unprecedented 80% of the Blue Mountains burned in what is remembered as the Black Summer bushfires. This was followed by floods, landslides and COVID-19 lockdowns.

Resilient Villages

Resilient Villages (supplied)

“It’s just been cascading disasters,” Kris said. “In 2021 we (MCRN) were successful in gaining a Disaster Risk Reduction Fund grant to do a pilot of Resilient Villages.”

We went out to impacted communities and essentially said: “You guys have just been through all of this. We’d be happy to help you figure out how to get yourself mobilised at the local level.”

Kris emphasises there is no “cookie cutter” approach to community work: different communities want and need different things. Learning from their experiences after 2013 and other community models of self-organising like the ‘People’s Republic of Mallacoota’, the Resilient Villages team listens deeply to what communities want or need, then offers connections and expertise, as well as “help with things like grant writing skills, governance issues, event planning, succession planning, a whole range of things that a local community group might need help with.”

ABCD Inc

An example of how Resilient Villages has supported community-led recovery and preparedness can be seen in the townships of Bell, Clarence and Dargan, where communities combined forces to create a cross-community representative body, ABCD Inc. (the Association of Bell Clarence and Dargan), in response to the devastating impact of the 2019 fires on their towns.

Dargan resident and president of ABCD Inc. Kevin McCusker said, “I saw people doing it hard, harder than it needed to be. Even though we were separate villages, we were all in the same fire. We experienced the same horrible things. When we started talking to each other, we realised we’d be stronger if we came together.”

The group had already formed when Resilient Villages approached them and asked if they could offer any help. “When we approached them, they had incorporated and were already looking for grants to rebuild the Community Hall (lost in the fires),” Kris said.

“They were looking to turn it into a local resilience hub – with a satellite phone, solar panels/battery, fridges and freezers for community events/Friday pizza night – a place to go to recharge your battery and find out what’s going on with a disaster, a community gathering place. So Resilient Villages has an MoU with ABCD Inc: even at that stage, they were very clear about what they needed and what assistance they thought the project could provide.”

Firewise Expo (supplied)

Another example is in Megalong Valley where Resilient Villages introduced the community to ABCD Inc. as a way of providing connections and examples of what’s possible.

“The output at the end of this pilot is that the participating villages will have a Resilience Action Plan,” said Kris. “Whether that’s a piece of paper, or a video, or something else, who knows, but there will be a locally endorsed ‘How are we going to do this better next time?’ action plan of some kind for each community.

From the community development point of view of course, that’s just the end destination. For us, the whole point is the journey each community takes along the way: capacity-building in local community, assisting them with the skills they need/want (e.g. of finding out who is in your community, how you engage your community, how you engage in a process of community consultation that captures the voices that don’t usually get heard); then coming up with a design that community agrees: ‘We think this will work for our community’.

It’s not a static thing, not a once-off. It’s something that probably needs to be reviewed every year or so.”

Preserving food from her garden is one way Kris makes the produce last all year round and provides her with food security in the case of emergency.

Kris’s vision is that we build resilient individuals, families, neighbourhoods and communities able to cope with shocks. We do this by changing the system from a top-down approach to recovery, preparedness and resilience to a spiral-up approach that starts in preschool and reaches the fringes of each community.

Her ‘Grand Vision’ is that eventually every village also has a ‘resilience hub’ like the one being established by ABCD Inc, “so there’s always somewhere to go at the end of the road. There’s always somewhere that you can go to get trusted sources of up-to-date information; where you can connect with your neighbours and community; where you can get food or support; or just charge your devices.”

Take Action:

- Get to know your neighbours! (Maybe think about setting up local support networks, especially those more at-risk in emergencies)

- ‘Prevention is better than cure’. Attend ‘Meet Your Street’ or similar preparedness activities in your community and find out how you can be better prepared for all kinds of emergencies (bushfires, of course, but also pandemics, severe storms, floods, snow: we have everything in the Mountains!)

- Start/join local or neighbourhood discussion groups around building more resilient local community (possibly through your local Neighbourhood Centre).

Share this article:

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.