Emeritus Professor Stuart Hill in his study. (Photo: Belle Butler)

Life is made up of complex systems in which everything is inter-connected. Over his decades-long teaching career, Stuart Hill, a retired Emeritus Professor, and Linden resident, has helped hundreds of students understand the critical links between human actions and the health of our planet.

Key Points:

- The interconnectedness of life systems: Professor Hill’s research on the ecosystem of a bat cave, and soil ecology, has highlighted the intricate relationships between organisms and their environment.

- The importance of holistic thinking: By studying entire ecosystems, Professor Hill emphasised the need to consider all components of a system, rather than focusing on individual elements.

- The potential of untapped resources: Professor Hill believes that understanding the unseen processes of nature, such as those occurring in soil, holds the key to addressing global challenges.

Professor Hill’s own thinking has stemmed from an everlasting love of, and connection with nature and has built on his early research as a zoologist in the mid 60s. His PhD involved the study of a bat cave in Trinidad: a complete, almost self-contained ecosystem in which it was actually possible to observe and measure all the complex relationships that create life. One of the smallest beetles in the world, that he discovered in that cave, is even named after him: Micridium hilli.

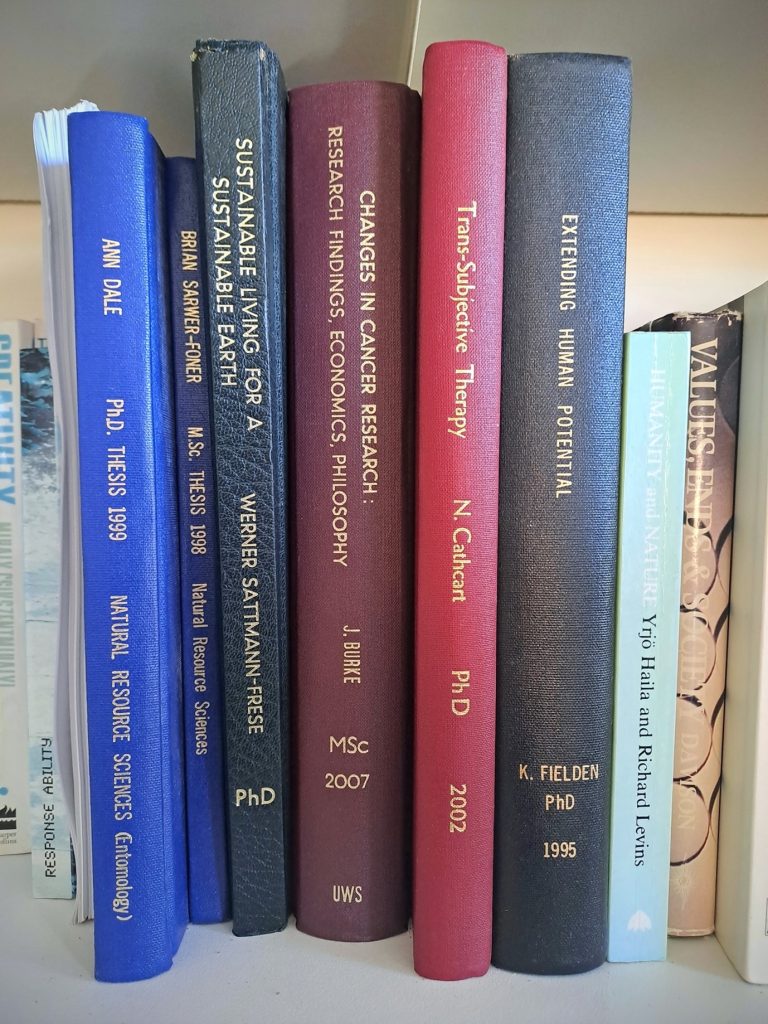

Ann Dale, his last PhD student at McGill University in Canada in the 70’s, went on to establish the government’s first ‘National Round Table for the Economy and the Environment’- recognising that our economies profoundly impact both human health and the health of the planet.

Emeritus Professor Stuart Hill has inspired the work of many students and contributed to many publications. (Photo: Belle Butler)

Once known as ‘Mr Organics’ he was responsible for facilitating the research in the 70s that validated the benefits of organic farming. Much of the experience that he brought to this derived from his early studies in the Bat cave in Trinidad.

Learning from the bat cave

Professor Hill’s recollections of his PhD research:

“There were a quarter of a million bats and all sorts of other things in the cave, but it turned out that most of the cave life was in the guano, the bat droppings. In much of the cave the guano was half a metre deep, and when I actually measured its respiratory rate I found it was respiring at the same rate as a domestic cat. That’s how dynamic it was. It was a heaving living mass because of the presence of microorganisms, microarthropods, cockroaches, and a range of other arthropods.”

“In the process I became interested in life in the soil, which was the closest thing to this guano. When I finished the work I was essentially writing up a PhD thesis on the ecology of a very special type of soil. I had gained an understanding of soil ecology, way beyond what anybody else had discovered. Up to that time, those studying life in the soil were specialising — they were looking at the fungi, or the bacteria, or the insect life, but not at the whole system. Whereas I was studying the whole system and studied energy flow and community relationships in the guano, which was just like a very fertile soil.”

“I also compared guano with soil outside the cave. Through my research, my interest shifted from a focus on marine ecology to a focus on soil and terrestrial ecology, and particularly the relationships between micro-arthropods, especially mites, and the fungi.”

“In soil there are really three sub ecosystems. Soil is made up of little particles and those particles are surrounded by a water film. In between there’s a space. Some organisms are living in the water film, particularly bacteria, protozoa, nematodes, rotifers and things that swim.”

“Then there are fungi that grow out into the air spaces, and a whole lot of animals, such as mites and springtails, that are dependent on those air spaces to walk around and feed on the fungi, similar to cows feeding on grass. What I discovered was that those organisms were actually ‘farming’ the fungi. Nobody had really understood this because they mostly looked at the various types of organisms separately.”

“The third sub ecosystem comprises the organisms that can actually move through the soil by creating spaces, such as earthworms. They’re not dependent on the spaces that already exist, they’re actually pushing through and creating their own spaces. We humans have a mucus lining in our gut, while in contrast micro-arthropods have an extension of their exoskeleton lining their gut. They’re covered in chitin outside and that actually extends all through their gut as a sleeve, or lining.”

“When they eat fungi they eat the hypha and the spores, and chomp it all up. They digest the hypha but not the spores, the spores survive. Each time they poo they cast off a little bit of the sleeve of the gut lining and inside that little faecal pellet, which is like compost, are fungal spores. When this faecal pellet is deposited in the soil the chitinous sleeve protects it from being accessed by fungi other than those that have germinated from the contained spores. So, in a sense, they are practicing ‘weed control’.”

Stuart argues that it is the things that we can’t see, in this case the life in the soil and the processes going on, and what goes on in our subconscious, that are in a sense our greatest hope for the future. They’re our greatest untapped resource.

Until he retired in 2009, Stuart spent more than 20 years as the Foundation Chair of Social Ecology at Western Sydney University, training many more young people in systems thinking. He firmly believes that social change requires a willingness to learn both from nature and from other people, to pay attention to ‘the things we can’t see’ and to take a holistic and pluralistic approach, in which we pay much more attention to practitioners on the ground who gain their wisdom from actual experience.

Share this article:

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.