Amy St Lawrence and Rob McCormack wearing crayfish hats at the most recent crayfish survey. (Photo: Will Goodwin)

Story by Belle Butler

In August 2023, a mass kill of freshwater spiny crayfish took place in a tributary to Hazelbrook Creek. Belle Butler talked to Blue Mountains City Council Aquatic Systems Officers Amy St Lawrence and Alice Blackwood about the incident, how recovery is going and what we can do to protect this keystone species.

Key Points:

- Giant Spiny Crayfish (Euastacus spinifer) and Sydney Crayfish (Euastacus australasiensis) are two iconic and long-lived Blue Mountains species that are vital to the health of whole ecosystems.

- Fishing and stormwater pollution are constant key threats to crayfish, while pesticide contamination, specifically the synthetic pyrethroid bifenthrin, has caused mass kill events in at least two local creeks.

- While recovery is underway in recently contaminated waterways, further research and action is required to bolster full recovery, maintain populations and healthy waterways, and prevent further devastation.

I was recently on a waterfall walk at Murphys Glen, Woodford, when I heard a rustle nearby. The sound sent my body into rigid alert as I anticipated the discovery of a snake.

I stood at the ready and scanned the surrounding scrub, only to discover the maker of this noise was not a slithery friend, but a spiny one.

There on the bank of a creek was a Giant Spiny Crayfish, boldly raising its claws at me. Clearly I had startled it too, as it was already on its retreat to the safety of the stream.

I watched it for a while longer, mesmerised by its threatening claws, its fancy armour and its constant gaze fixed firmly on me as it scuttled backwards before dropping into a foliage-fortified hidey-hole.

Giant Spiny Crayfish after retreating to the safety of a creek in Woodford. (Photo: Belle Butler)

This little creature’s survival instinct seemed fierce, as if it was ready and willing to go into battle despite my giant-status in comparison. However, while it may conjure up visions of an armoured warrior, the Giant Spiny Crayfish, and its local cousin, the Sydney Crayfish, are more vulnerable than they appear.

In August 2023 approximately 1000 crayfish were killed at a tributary to Hazelbrook Creek, Hazelbrook, when the insecticide bifenthrin entered the waterway.

Bifenthrin is used domestically and by businesses to control termites and other ‘pests’ such as a spiders, ants, fleas, flies and mosquitos. It is a third generation synthetic pyrethroid that binds to sediment and has a relatively high environmental persistence time (the amount of time a chemical remains in the environment).

Dead crayfish found after the bifenthrin contamination at a tributary to Hazelbrook Creek, 2023. (Photo: Amy St Lawrence)

As evidenced in the Hazelbrook incident, and at a similar mass kill event in Jamison Creek (2012), Bifenthrin is devastatingly toxic to crayfish, as well as to terrestrial and aquatic insects, other crustaceans and, to a lesser degree, fish.

On March 4 2024, the EPA released a media report on its investigation of the Hazelbrook incident, which stated that one individual was fined $8,250 after accidentally spilling nearly 40 litres of diluted Bifenthrin on their private driveway, which then flowed into the stormwater system. The incident was deemed preventable.

“The individual had the opportunity to clean up the spill to prevent further harm but failed to do so,” EPA Executive Director of Regulatory Operations, Jason Gordon said. “While we are pleased the person responsible came forward on their own accord, we are committed to holding individuals accountable for actions that endanger our precious ecosystems.”

The event at Jamison Creek in 2012 was found to be a result of attempted pest control at a residential development in Wentworth Falls. One company and one individual pleaded guilty in Katoomba Local Court to water pollution offences after over-applying bifenthrin by approximately 53%.

“Both the 2012 Jamison Creek and the 2023 Hazelbrook Creek bifenthrin incidents are important illustrations of the dangers of direct stormwater connections between urban areas and waterways,” said Amy St Lawrence from the Healthy Waterways Team at Blue Mountains City Council. “At Jamison, the pesticide was over-applied at a private property 300m away from the creek, but when it rained that night, bifenthrin was washed straight into the property’s stormwater pit and directly into the creek through a series of underground pits and pipes.

“At Hazelbrook Creek, bifenthrin was accidentally spilled on the driveway of a private property and flowed through the stormwater system, straight into the creek. Throughout the Blue Mountains, many houses, roads, town centres, carparks and other impervious surfaces remain directly connected to creeks via conventional drainage systems of pits and pipes, kerbs and gutters. This makes it far too easy for pollution to get into our waterways, along with damaging runoff volumes that cause erosion and sedimentation in our creeks and swamps.”

Alice Blackwood collecting crayfish carcasses in Hazelbrook, 2023. (Photo: Amy St Lawrence)

Witnessing the preventable annihilation of whole crayfish populations is upsetting for many locals, and particularly devastating for those in the Healthy Waterways Team who work hard to protect these creatures.

“These mass kill events are really very upsetting,” said Amy. “At Hazelbrook it was awful seeing so many hundreds of dead crayfish, from tiny babies to big, berried females [with eggs]. Seeing them still alive but upside down and struggling and knowing they were not going to survive was almost worse than finding the dead ones.”

Crayfish are a keystone species. This means their existence helps to keep the whole ecosystem functioning. “Mature female crayfish produce hundreds of young each year, but possibly fewer than one in 1000 survive until adulthood,” Alice Blackwood from the Healthy Waterways Team explained. “The rest of the young are an important food source to other fauna in the creeks, such as platypus, turtles, eels, rakali, and fish. They are also scavengers, and they play an important role in nutrient cycling, cleaning up fallen organic matter in waterways.”

Beyond their importance in aquatic ecosystems, crayfish are an iconic, long-lived species. They can possibly live up to around 80 years, and mature crayfish typically stay in one area their whole lives. That means you can potentially make a life-long friend with one in your local streams!

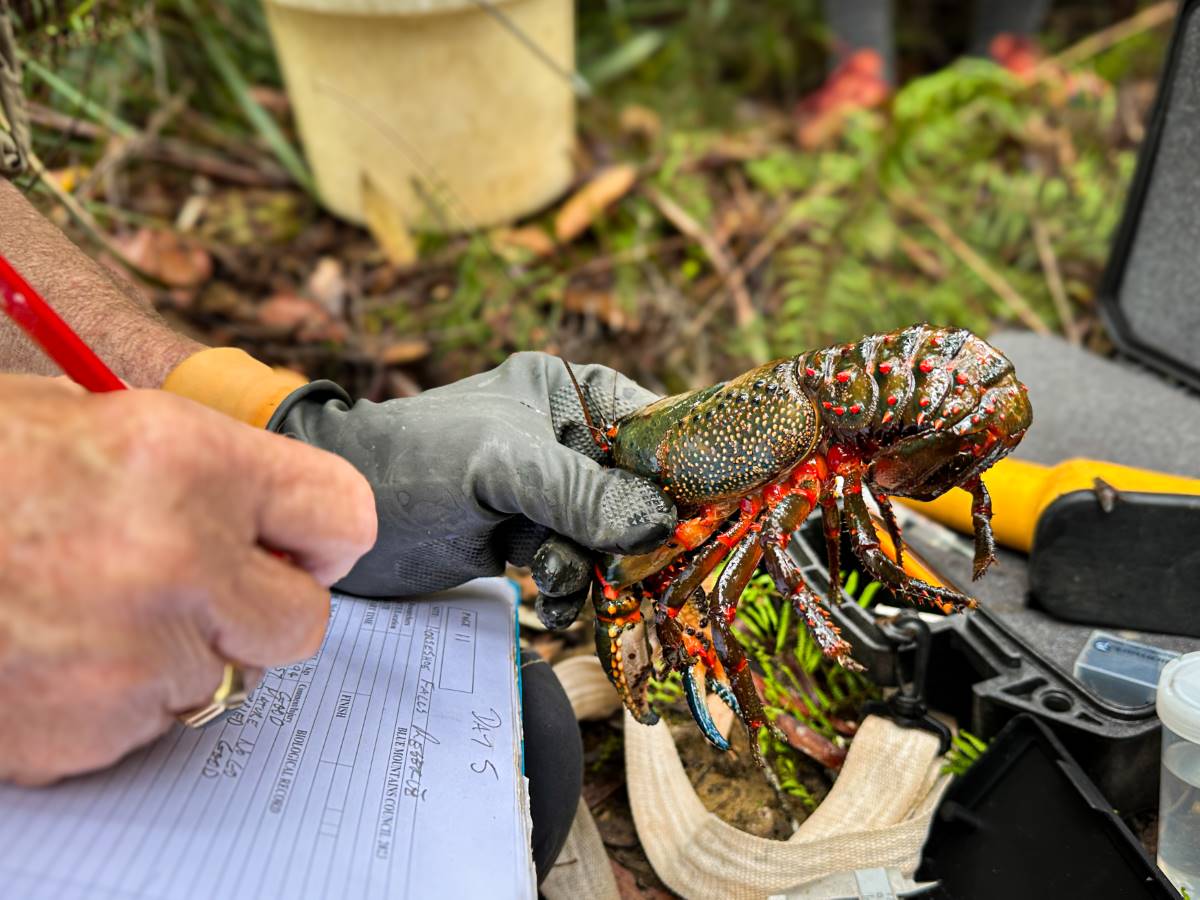

Healthy Giant Spiny Crayfish found in Hazelbrook at the 2023 Crayfish Survey (Photo: Will Goodwin)

So, what are we doing to protect them?

The Healthy Waterways Team conduct annual crayfish surveys, in partnership with survey-lead and crayfish researcher Rob McCormack. Now with nine surveys completed, they have collected important data about these longtime Blue Mountains aquatic residents, such as growth rates, movement from year to year, and breeding success, as well as information about their rate of recovery after disastrous events such as the bifenthrin mass kill in Hazelbrook.

Promisingly, a recent survey conducted in November 2023 showed early signs of crayfish recovery in the tributary to Hazelbrook Creek. “At Hazelbrook Creek it appeared that crayfish are recolonising the affected section of creek from nearby feeder streams both above and below the affected area,” reported Alice. “In the middle part of the affected area we didn’t find any crayfish. Hopefully by next year’s survey, numbers will have increased further and also spread to this section of creek.”

Crayfish researcher Rob McCormack with a Giant Spiny Crayfish at the recent crayfish survey in Hazelbrook. (Photo: Amy St Lawrence)

This is consistent with a pattern of resilience and recovery that followed the Jamison Creek bifenthrin kill in 2012. “Our results tell us that in general our creeks are quite resilient, and we are lucky to have these amazing creatures living so close to urban areas. The crayfish can be seen as indicators of water quality and habitat condition, and in creeks such as Jamison they tell us a positive story. Notably, this is also a catchment in which we have constructed a large number of raingardens,” Alice said.

While data from the 2023 survey has shown some positive trends in Hazelbrook and Jamison Creeks, Amy and Alice reported that crayfish numbers are “concerningly low” in Leura Falls Creek, and that sediment sampling has shown that synthetic pyrethroid pesticides, such as bifenthrin, are found in concerning levels in many creeks throughout the Blue Mountains.

Taking measurements at the recent Blue Mountains Crayfish Survey in Hazelbrook. (Photo: Will Goodwin)

The Healthy Waterways Team track this kind of information via a range of water monitoring programs aimed at building a scientific knowledge base to inform management of water in the Blue Mountains. “Our key waterway health monitoring program has now been running for 25 years, involving annual surveys at over 70 sites, using water bugs (aquatic macroinvertebrates) as indicators of health,” said Alice.

“We are working towards a vision of a water sensitive city, as outlined in the Water Sensitive Blue Mountains Strategic Plan. Implementing this plan will protect crayfish as well as the rest of our aquatic ecosystems. This includes catchment restoration projects where we have been installing raingardens, also known as biofiltration systems, at key stormwater outlets to filter out pollutants before stormwater hits the creeks. Our Connect With Nature education programs are also aiming to build the knowledge and skills in the community to protect crayfish, and our waterways more broadly.”

Amy added: “We desperately need the help of homes, businesses and all types of properties to manage their runoff at the source and ‘disconnect’ from creeks as much as possible.” She suggested installing rainwater tanks plumbed into toilet and laundry, building raingardens, minimising hard surfaces and maximising permeable areas where water can soak into the ground rather than contribute to runoff and pollution problems.

Amy in her raingarden at her home in Blackheath (Photo: Hamish Dunlop)

“I have loved the process of making my own home more ‘water sensitive’ by building a raingarden and installing a rainwater tank that collects our roof runoff and supplies that water to flush our toilets, wash our clothes and feed our hot water system. This helps feed my hope about what’s possible and I’m excited about these types of multi-benefit solutions and hopefully seeing them become the norm over time, rather than the old ‘pipe it out of sight and out of mind’ approaches” said Amy.

Read about Amy’s water sensitive efforts and what you can do to manage your water runoff here.

While further investigation and action is needed to facilitate recovery and maintain healthy waterways and crayfish populations, there is a lot we can do as a community to help. If you spot a crayfish, enjoy the experience! Amy and Alice also encourage you to help track numbers by participating in the Blue Mountains Crayfish Count on iNaturalist and report any sightings of dead or sick-looking crayfish to Blue Mountains City Council.

Further Reading:

A Guide To Australia’s Spiny Freshwater Crayfish – Robert McCormack

Water Sensitive Blue Mountains Strategic Plan

Bifenthrin pesticide contamination: impacts and recovery at Jamison Creek, Wentworth Falls.

Waterway health and stormwater management at Jamison Creek, Blue Mountains

Take Action:

- Choose eco-friendly pest treatment options, and minimise chemical use on your property

- Leave crayfish in place when you see them

- Keep pollutants such as dog poo, grass clippings and sediment out of gutters and stormwater drains

- Report illegal fishing to the Fishers Watch Phoneline on 1800 043 536

- Contribute to the Blue Mountains Crayfish Count

- Make your home or business more ‘water sensitive’ by reducing stormwater runoff from your property. e.g. by installing a rainwater tank and using the water in your toilet, laundry and garden, and building a raingarden.

- Report pollution: NSW Environment Line 131 555 and/or Blue Mountains City Council

- Report sewage leaks: Sydney Water 13 20 90 and/or Blue Mountains City Council

Share this article:

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.